- Study

- Slides

- Videos

9.1 Comonly Used Jargons in Stock Market

Vedant: Hey Nirav, I see you’ve been checking stock prices a lot lately. Getting into trading?

Nirav: Yeah, trying to learn. But I keep hearing weird words—bull market, short selling, circuits… feels confusing.

Vedant: Totally normal. The stock market has its own language. Once you understand these common terms, everything starts to make sense.

Nirav: So learning the lingo is the first step?

Vedant: Exactly! Let’s go over the most used words, simple and clear, so you can understand what’s really happening in the market.

-

Bull Market – A market condition where prices are rising or expected to rise.

A bull market is a prolonged period where stock prices rise steadily, often by 20% or more from recent lows. It reflects strong investor confidence, robust economic indicators like GDP growth and low unemployment, and is typically fuelled by high liquidity and positive corporate earnings. During such times, investors are optimistic, IPOs flourish, and risk appetite increases across the board.

Example: Ramesh ran a modest tea stall near the local bus stand. Every morning, a group of retired uncles gathered there, discussing everything from politics to cricket. One day, a young man named Aarav, fresh from the city, started frequenting the stall—not for tea, but for the Wi-Fi and his stock trading app.

The old timers were skeptical. “Stocks? It’s like gambling,” one said. But week after week, Aarav kept smiling. He showed them how the Sensex had climbed steadily post-election, how IT stocks had surged, and how foreign investors were pouring money into Indian equities. He explained terms like “liquidity,” “earnings season,” and “macro tailwinds,” but all the uncles heard was: “market upar jaa raha hai.”

Curious, Ramesh took a leap—he invested ₹10,000 in an index fund Aarav recommended.

Months passed. The town watched as Ramesh’s humble tea stall got a fancy new board, new cups, and even a QR code scanner. His investment had grown by 35% in less than a year. “Bull market,” Aarav smiled, sipping his chai. “Even a cup of tea tastes sweeter when the market’s on your side.”

-

Bear Market – A market phase where prices are falling or expected to fall.

A bear market is the opposite—a sustained decline of 20% or more in stock prices, often triggered by economic slowdowns, rising interest rates, or geopolitical tensions. Investor sentiment turns pessimistic, leading to widespread selling and reduced valuations. While it can be unsettling, seasoned investors often view bear markets as opportunities to accumulate quality stocks at discounted prices.

Example – A classic example of a bear market occurred during the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. Triggered by the collapse of the U.S. housing bubble and the failure of major financial institutions like Lehman Brothers, global stock markets plummeted. The S&P 500, for instance, fell over 50% from its 2007 peak to its 2009 low. Investor sentiment turned deeply pessimistic, credit markets froze, and economies around the world slipped into recession. In India, the Sensex dropped from around 21,000 in January 2008 to below 9,000 by October the same year. This prolonged downturn, marked by fear and uncertainty, is a textbook case of a bear market

-

Trend – The general direction in which the market or a stock is moving (uptrend, downtrend, sideways).

A trend refers to the general direction in which a stock or the overall market is moving. It can be upward (uptrend), downward (downtrend), or sideways (range-bound). Identifying trends is crucial for technical analysis, as it helps traders align their strategies with market momentum. For instance, higher highs and higher lows indicate an uptrend, while lower highs and lower lows suggest a downtrend.

Example – A great example of a market trend can be seen in the uptrend of Indian IT stocks between 2016 and early 2021. During this period, companies like Infosys, TCS, and Wipro consistently posted strong earnings, benefited from global digital transformation, and attracted both domestic and foreign investor interest. Their stock prices formed a pattern of higher highs and higher lows on the charts—classic signs of an uptrend. Conversely, in early 2020, during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the market experienced a sharp downtrend, with indices like the Nifty 50 and Sensex falling rapidly due to panic selling and economic uncertainty. In contrast, a sideways trend was observed in mid-2022 when the market moved within a narrow range, reflecting indecision among investors amid inflation and interest rate concerns

-

Face Value – The nominal value of a share, important for corporate actions like dividends and splits.

Face value, also known as par value, is the original nominal value assigned to a share by the company at the time of issuance—commonly ₹1, ₹2, ₹5, or ₹10 in India. It plays a key role in accounting and corporate actions like dividends, stock splits, and bonus issues. While it doesn’t reflect the market price, it’s essential for calculating share capital and understanding a company’s financial structure.

Example–Imagine a company issues 1,00,000 shares with a face value of ₹10 each. This means the company’s share capital is ₹10 lakhs (1,00,000 × ₹10). Now, even if the stock is trading in the market at ₹500, the face value remains ₹10—it’s the nominal value recorded in the company’s books. This face value becomes important during corporate actions. For instance, if the company declares a 100% dividend, it means shareholders will receive ₹10 per share (100% of ₹10), not ₹500. Similarly, if the company announces a stock split from ₹10 to ₹5 face value, each shareholder will receive 2 shares for every 1 held, and the market price adjusts accordingly.

-

52-Week High/Low – The highest and lowest price a stock has traded at in the past year.

The 52-week high and low represent the highest and lowest prices at which a stock has traded over the past year. These levels are closely watched by investors and traders as psychological benchmarks. A stock nearing its 52-week high may signal bullish momentum, while one approaching its 52-week low might indicate undervaluation—or deeper issues requiring scrutiny.

Example -As of June 2025, Aditya Birla Capital Ltd recently hit its 52-week high, meaning it reached the highest price it has traded at in the past one year. On the flip side, Protean eGov Technologies Ltd touched its 52-week low, marking the lowest price it has seen during the same period. These levels are closely watched by traders and investors because they often act as psychological benchmarks—stocks near their 52-week high may signal bullish momentum, while those near their 52-week low might indicate undervaluation or deeper concerns.

-

All-Time High/Low – The highest or lowest price a stock has ever reached since listing.

An all-time high or low refers to the absolute highest or lowest price a stock has ever traded at since it was listed on the stock exchange. These levels are often seen as psychological milestones—when a stock hits an all-time high, it may signal strong investor confidence or bullish momentum, while an all-time low might reflect distress, undervaluation, or broader market pessimism. Traders and investors closely watch these levels to assess sentiment, set targets, or identify potential reversals.

Example– A strong example of an All-Time High in India is MRF Ltd, which reached a staggering price of ₹1,51,445 per share—making it the most expensive stock on the Indian exchanges in absolute terms. On the flip side, consider Bombay Oxygen Investments Ltd, which once traded at an all-time low of ₹2,505 before surging dramatically in later years. These extremes reflect not just company performance but also investor sentiment, sectoral trends, and broader market cycles. All-time highs often attract momentum traders, while all-time lows may catch the eye of value investors looking for a turnaround story.

-

Upper/Lower Circuit – The maximum price range a stock can move in a day, set by the exchange to control volatility.

Upper and lower circuits are daily price bands set by stock exchanges to prevent extreme volatility in a stock’s price. The upper circuit is the maximum price a stock can rise to in a single trading session, while the lower circuit is the lowest it can fall. If a stock hits either limit, trading may be temporarily halted to cool off excessive speculation or panic. These mechanisms are especially important in non liquid or news-sensitive stocks, helping maintain orderly market Behavior and protect investors from sudden price shocks.

Example- Upper and Lower Circuits in action occurred during the Adani Group stock volatility in early 2023. After the release of a critical report by a U.S.-based short seller, several Adani stocks—like Adani Total Gas and Adani Transmission—hit their lower circuit limits multiple days in a row, meaning their prices fell to the maximum permissible limit for the day and trading was temporarily frozen to prevent panic selling. Conversely, when investor sentiment later improved, some of these stocks hit their upper circuit limits, rising to the maximum allowed level in a single session, triggering a temporary halt in buying.

These circuit limits—typically set at 5%, 10%, or 20% depending on the stock’s category—are designed by exchanges like NSE and BSE to curb excessive volatility and protect investors from irrational price swings

-

Square Off – Closing an existing position (e.g., selling a stock you bought earlier).

To square off means to close an open position in the market—either by selling a stock you’ve bought or buying back a stock you’ve short-sold. This is a common practice in intraday trading, where all positions must be squared off before the market closes. If a trader forgets to do it manually, most brokers will automatically square off the position near the end of the session, often between 3:15 and 3:20 PM. It ensures that no open positions are carried overnight, avoiding exposure to after-hours market risks.

-

Intraday Trading – Buying and selling stocks within the same trading day.

Intraday trading involves buying and selling stocks within the same trading day, with the goal of profiting from short-term price movements. Unlike long-term investing, intraday traders don’t take delivery of shares—they simply capitalize on volatility and exit before the market closes. It requires quick decision-making, technical analysis, and strict discipline, as even small price swings can lead to gains or losses. Since trades are squared off the same day, there’s no overnight risk, but the fast pace makes it riskier for beginners.

Example– Let’s say Arjun, an active trader, notices that Tata Motors is showing strong momentum in the morning session due to positive quarterly results. The stock opens at ₹780 and quickly starts climbing. Arjun buys 200 shares at ₹785 around 10:15 AM, anticipating further upside. By 1:30 PM, the stock touches ₹805. Satisfied with the ₹20 per share gain, he sells all 200 shares, locking in a profit of ₹4,000—all within the same trading day. Since he didn’t hold the stock overnight and squared off the position before market close, this is a classic example of intraday trading.

-

Delivery Trading – Buying stocks and holding them beyond the trading day.

Delivery trading refers to buying stocks and holding them beyond the trading day, with the shares being credited to your demat account. This is the traditional form of investing, where you can hold stocks for days, months, or even years, depending on your financial goals. Delivery trading allows you to benefit from dividends, bonus issues, and long-term capital appreciation. It’s ideal for investors who prefer a patient, research-driven rather than chasing short-term market movements.

Example– Suppose Meera believes in the long-term growth of the Indian renewable energy sector. On Monday, she buys 50 shares of Tata Power at ₹320 each through her trading platform. Instead of selling them the same day, she holds onto the shares, which are credited to her demat account by T+1 (the next trading day). Over the next few months, as the company announces new solar projects and posts strong earnings, the stock price gradually rises to ₹390. Meera decides to sell her shares after six months, booking a profit of ₹70 per share. Since she held the shares beyond the trading day and took delivery into her demat account, this is a classic case of delivery trading—ideal for investors who prefer a patient, long-term approach.

9.2 Commonly Used Jargons in Stock Market

-

Short Selling – Selling a stock you don’t own, hoping to buy it back at a lower price.

Short selling is a trading strategy where an investor sells shares they don’t actually own, with the intention of buying them back later at a lower price. This is done by borrowing the shares from a broker and selling them in the market. If the stock price falls as expected, the trader can repurchase the shares at the lower price, return them to the lender, and pocket the difference as profit. However, if the price rises instead, losses can be unlimited, making short selling a high-risk, high-reward strategy often used by experienced traders or for hedging purposes.

Example- Imagine Vikram believes that shares of XYZ Ltd, currently trading at ₹800, are overvalued and likely to fall. He borrows 100 shares from his broker and sells them immediately in the market, pocketing ₹80,000 (₹800 × 100). A few days later, the stock drops to ₹720. Vikram then buys back the 100 shares for ₹72,000 and returns them to the broker. His profit? ₹8,000—minus any brokerage or borrowing costs. This is a classic short sell: selling high first, then buying low later to profit from the price drop.

However, if the stock had risen instead—say to ₹850—he would have faced a loss of ₹5,000. That’s why short selling carries high risk and is typically used by experienced traders or as a hedge against long positions

-

Long Position – Buying a stock with the expectation that its price will rise.

Taking a long position means buying a stock with the expectation that its price will rise over time. It’s the most common and straightforward investment approach—buy low, sell high. Investors who go long believe in the company’s growth potential and typically hold the stock for a period ranging from days to years. This strategy benefits from capital appreciation and, in some cases, dividends, making it ideal for those with a bullish outlook on the market or a specific stock.

Example- Ananya believes that Reliance Industries is poised for strong growth due to its expansion in green energy and digital services. On Monday, she buys 100 shares of Reliance at ₹2,500 each, expecting the price to rise over the coming months. She holds the shares in her demat account, monitoring company updates and market trends. By October, the stock climbs to ₹2,950. Confident she’s met her target, Ananya sells all 100 shares, earning a profit of ₹45,000. Since she bought the stock with the expectation of a price increase and held it until it appreciated, this is a textbook example of a long position.

-

Stop Loss – A pre-set price to automatically exit a trade to limit losses.

A stop loss is a risk management tool that allows traders to set a predetermined price at which their position will be automatically sold to prevent further losses. For example, if you buy a stock at ₹500 and set a stop loss at ₹470, your broker will trigger a sell order if the price drops to ₹470, limiting your loss to ₹30 per share. It’s especially useful in volatile markets, helping traders avoid emotional decision-making and protect their capital from sharp downturns.

Example- Suppose Neha buys 100 shares of Infosys at ₹1,500 each, expecting the price to rise. However, she also wants to protect herself in case the market moves against her. So, she places a stop-loss order at ₹1,450. This means if the stock price drops to ₹1,450, her broker will automatically sell the shares to limit her loss to ₹50 per share. If the price never falls to ₹1,450, the stop loss remains inactive, and she continues holding the stock. But if the market dips sharply and hits ₹1,450, the stop-loss order is triggered, and her position is exited—helping her avoid deeper losses.

-

Support Level – A price level where a stock tends to stop falling due to demand.

The support level is a price point at which a stock tends to stop falling and may start to rebound due to increased buying interest. It acts like a psychological or technical “floor” where demand outweighs supply. Traders often use support levels to identify potential entry points, assuming the price will bounce back. If the support is broken, it may signal further downside, but if it holds, it reinforces the level’s strength and investor confidence.

A great example of a support level in action was seen with Infosys Ltd during the market correction in early 2022. After a sharp decline, the stock consistently found buying interest around the ₹1,350 mark. Every time the price approached this level, demand increased, and the stock bounced back—indicating that ₹1,350 had become a strong support zone. Traders and investors viewed this level as a bargain entry point, reinforcing the idea that support levels are where buyers step in to prevent further decline. Eventually, when Infosys broke below this support due to broader market weakness, it signalled a potential trend reversal, showing how critical these levels can be in technical analysis

-

Resistance Level – A price level where a stock tends to stop rising due to selling pressure.

Resistance level is the opposite of support—it’s the price point where a stock tends to stop rising due to increased selling pressure. It acts like a “ceiling” that the stock struggles to break through. When a stock approaches resistance, traders may take profits, causing the price to stall or reverse. However, if the stock breaks above this level with strong volume, it can signal a bullish breakout and lead to further upward momentum.

Example- A clear example of a resistance level was seen in Tata Consultancy Services (TCS) during mid-2021. The stock repeatedly approached the ₹3,900–₹4,000 range but struggled to break above it. Each time it neared this zone, selling pressure increased—investors likely booked profits or anticipated a reversal—causing the price to retreat. This created a visible ceiling on the chart, marking it as a strong resistance level. Only after multiple attempts and a strong earnings report did TCS finally break through, triggering a bullish breakout. Such resistance zones are closely watched by traders to time entries, exits, or set stop-loss levels.

-

Volume – The number of shares traded during a specific period; indicates interest and liquidity.

Volume refers to the total number of shares traded in a stock or across the market during a specific time frame—be it a minute, a day, or a month. It reflects the level of activity and investor interest in a particular security. High volume often indicates strong participation and liquidity, making it easier to enter or exit positions without significantly impacting the price. Traders also use volume to confirm trends; for instance, a price rise accompanied by high volume is considered more reliable than one with low volume.

Example– Let’s say on a particular trading day, HDFC Bank sees 10 lakh shares bought and sold on the NSE. That means its trading volume for the day is 10 lakh shares. If the next day, the volume jumps to 25 lakh shares—perhaps due to a major earnings announcement or news event—it signals heightened investor interest and stronger liquidity. Traders often use such spikes in volume to confirm the strength of a price move. For instance, if HDFC Bank’s stock rises sharply on high volume, it’s considered a more reliable uptrend than a similar price move on low volume

-

Volatility – The degree of price fluctuation in a stock or market.

Volatility measures how much and how quickly a stock’s price fluctuates over time. A highly volatile stock experiences sharp price swings in either direction, while a low-volatility stock moves more steadily. Volatility is often seen as a proxy for risk—higher volatility means greater uncertainty but also greater potential for profit or loss. It can be influenced by market news, earnings reports, geopolitical events, or even investor sentiment, and is a key factor in pricing options and managing risk.

Example– A vivid example of volatility was seen during the COVID-19 market crash in March 2020. Global stock markets, including India’s Nifty 50 and Sensex, experienced wild price swings—falling over 30% in just a few weeks. One day the Sensex would drop 2,000 points, and the next it might rebound sharply, reflecting extreme uncertainty and fear among investors. This kind of rapid up-and-down movement is a textbook case of high volatility. It wasn’t just about the direction of the market—it was the speed and magnitude of the price changes that defined the volatility.

-

Market Order – An order to buy/sell immediately at the best available price.

Market Order is a type of trade instruction where an investor tells the broker to buy or sell a stock immediately at the best available price. It prioritizes speed over price precision, making it ideal when quick execution is more important than getting a specific rate. For example, if you place a market order to buy a stock trading around ₹500, your order will be filled instantly—though the final price may vary slightly depending on liquidity and order book depth.

Example- Suppose Raj wants to buy 50 shares of Infosys, which is currently trading at around ₹1,500. He places a market order through his broker, which means he’s willing to buy the shares at the best available price right now—without setting a specific price. The order gets executed instantly, but the actual price he pays might vary slightly depending on the current bids in the market. For instance, he might end up buying 20 shares at ₹1,501 and the remaining 30 at ₹1,503, depending on available sellers. The key point is: speed over price precision.

Market orders are ideal when execution speed matters more than getting a specific price—like in fast-moving or highly liquid stocks.

-

Limit Order – An order to buy/sell at a specific price or better.

Limit Order allows an investor to set a specific price at which they want to buy or sell a stock. The order will only be executed if the market reaches that price or better. For instance, if you place a buy limit order at ₹480 for a stock currently trading at ₹500, the trade will only go through if the price drops to ₹480 or lower. This gives you price control but no guarantee of execution, especially in fast-moving or illiquid markets.

Example- Suppose Aisha wants to buy shares of Tata Steel, currently trading at ₹150. However, she believes the stock is slightly overvalued and wants to enter only if the price drops. So, she places a buy limit order at ₹145. This means her order will only execute if the stock price falls to ₹145 or lower. If the price never drops to that level, the order remains unfilled. On the flip side, if she already owns the stock and wants to sell it only if it rises, she could place a sell limit order at ₹160, which will execute only if the price reaches ₹160 or higher.

Limit orders give traders price control, but not execution certainty—perfect for those who prioritize value over speed.

-

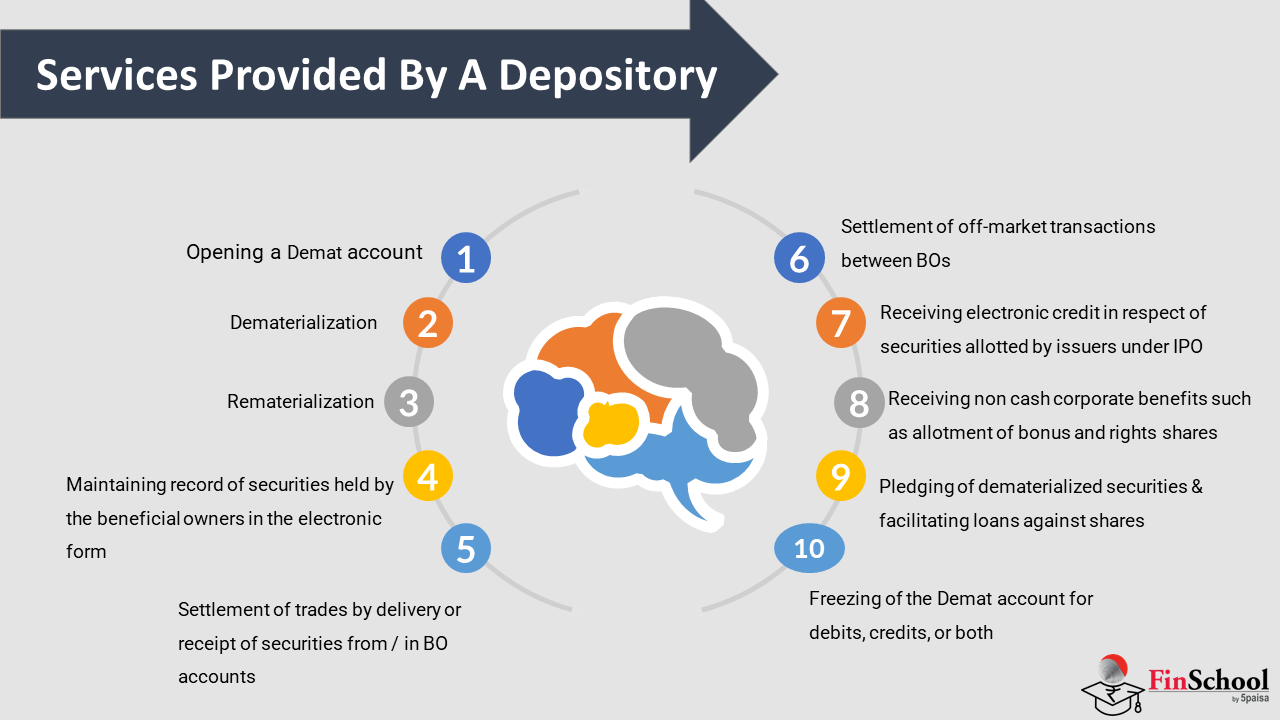

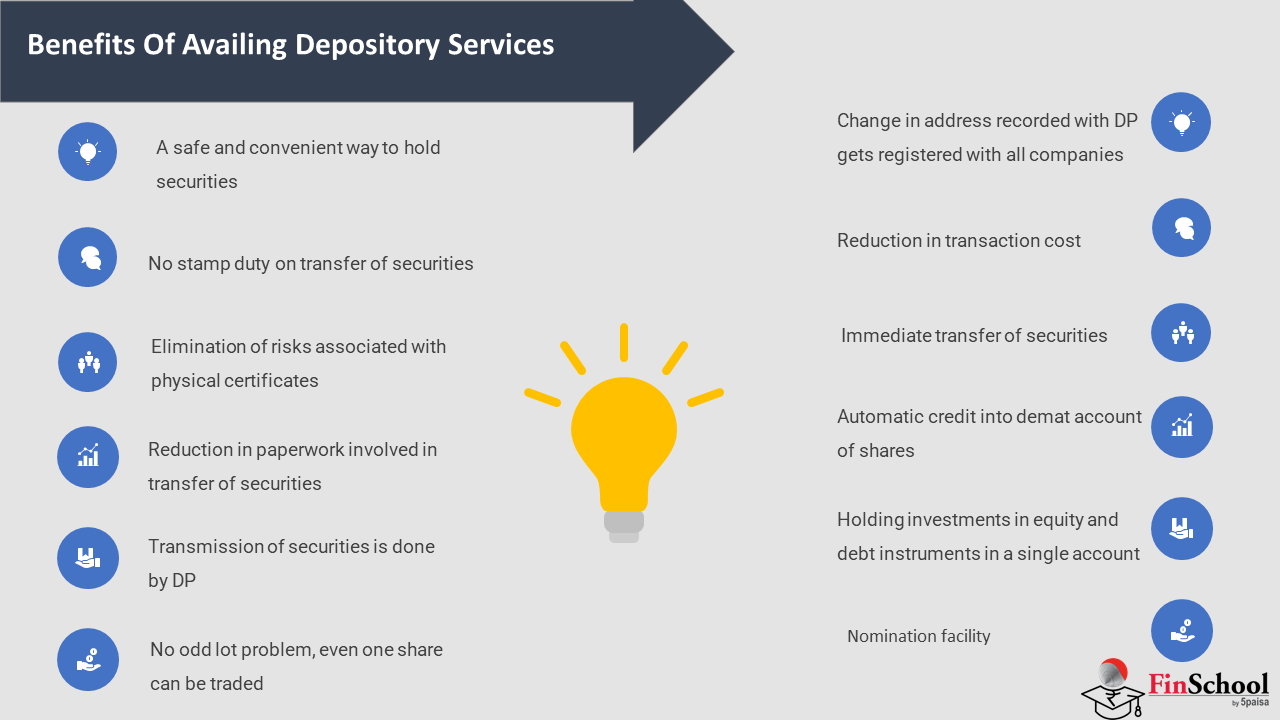

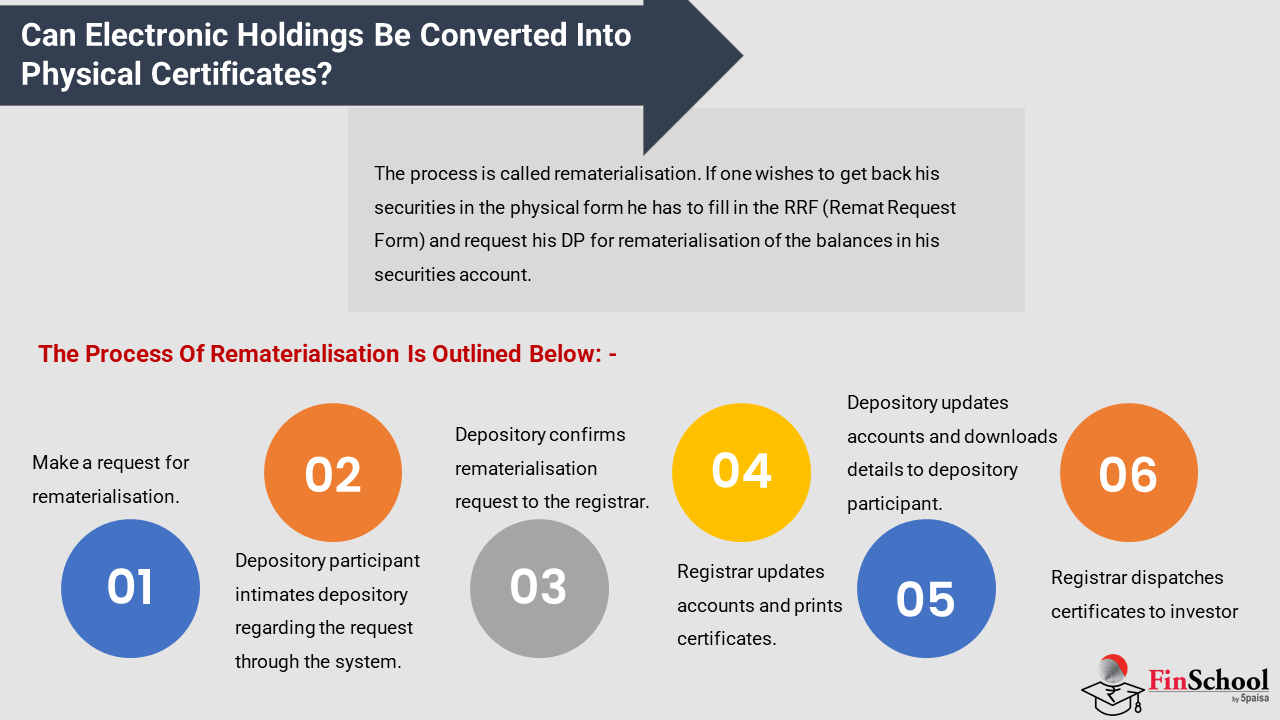

Demat Account – An account that holds your shares in electronic form, like a digital locker.

Demat Account (short for dematerialized account) is an electronic account that holds your shares and securities in digital form, eliminating the need for physical share certificates. It acts like a secure online locker, allowing you to buy, sell, and store stocks, mutual funds, bonds, and ETFs seamlessly. Regulated by depositories like NSDL and CDSL in India, a demat account is essential for modern investing and is linked to your trading and bank accounts for smooth transactions and corporate benefits like dividends and bonuses.

Example- Ravi wants to invest in shares of Infosys. He opens a Demat account with a broker like 5paisa. On Monday, he buys 100 shares of Infosys through his trading account. Instead of receiving physical share certificates, the shares are credited electronically to his Demat account by the next day (T+1 settlement). Over time, he also receives dividends directly into his linked bank account, and any bonus shares or stock splits are automatically updated in his Demat holdings. When he decides to sell the shares, the transaction is processed digitally, and the shares are debited from his Demat account. Just like a digital locker, the Demat account securely holds all his investments—stocks, mutual funds, bonds—in one place, making investing seamless and paperless.

Nirav: Vedant, I’ve got to admit, what felt like a maze of confusing terms now actually makes sense. Bull markets, circuits, stop loss… they aren’t just jargon anymore.

Vedant: Exactly. The stock market speaks a language, and once you learn it, you’re no longer just observing price movements, you’re interpreting what’s really happening beneath the surface.

Nirav: And the examples helped a lot. It’s one thing to read definitions, but seeing how they play out in real-life situations made it relatable.

Vedant: That’s the trick. Finance isn’t just about numbers, it’s about behavior, context, and decisions. Every term reflects a strategy or mindset that traders use daily.

Nirav: So next time I hear someone say “the stock hit its resistance,” I’ll know they’re not just tossing jargon, they’re reading the market’s mood.

Vedant: You’ve got it. Mastering the lingo is like sharpening your tools. Now you’re ready to move from theory to practice, just remember, continuous learning is key.

Nirav: Thanks for being my translator through this financial dialect.

Vedant: Anytime. The market doesn’t wait, but knowledge gives you the confidence to keep pace.